Research in focus: The TRIAD study - How PTSD develops in UK Armed Forces personnel

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) is a mental health diagnosis often linked to the military. A poll found that 83% of the British public thought PTSD was the greatest mental health problem affecting the military, despite alcohol misuse and depression actually being more common. Findings from the KCMHR cohort study highlighted, however, that some subgroups of the Armed Forces had higher rates of probable PTSD, e.g. rates were 17% among ex-regulars deployed to Iraq or Afghanistan in combat roles compared to 4% among those still in service.

The Forces in Mind Trust (FiMT) funded a study conducted by our department called ‘The TRaumatic exposures in Iraq and Afghanistan and responses of Distress’ (TRIAD) responding to these findings. We explored how PTSD symptoms might develop among the UK Armed Forces using multiple methods. Full findings can be found in a report launched on 19th January 2021.

Aim 1 The main patterns of PTSD: Key findings

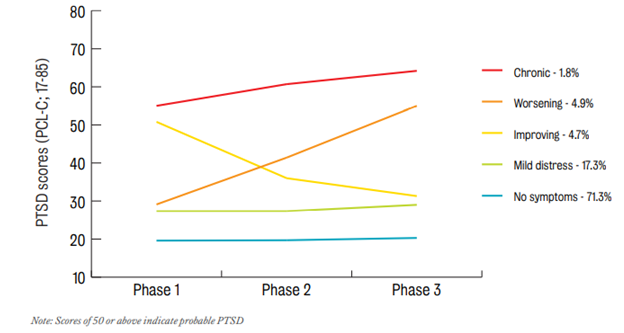

We firstly examined how symptoms changed from 2004 to 2016 using data from the King’s cohort study. Data were taken from self-completed questionnaires investigating the health and wellbeing of over 7,000 serving and ex-serving personnel [1]. We did this by running statistical models to draw out the main patterns of PTSD symptoms in the sample.

- Overall, 71% of the cohort consistently had no (or minimal) symptoms of PTSD over the twelve-year period;

- Our analysis also found a subgroup of 17% with raised symptoms, which we termed ‘mild distress’, but this was below the level often used for a diagnosis of PTSD;

- In total, 12% had probable PTSD at one point over the twelve-year period. Of these, 5% worsened over the time period; 5% showed improvements, and 2% had probable PTSD throughout the twelve-year period (Figure 1).

We then explored the patterns for those still in service v. those who had left. Patterns were largely similar, but we found more ex-serving than serving personnel (13% v. 10%) had probable PTSD overall; fewer ex-serving personnel recovered and if ex-serving personnel had PTSD throughout the 12 years, they also appeared to be getting worse.

Symptoms were linked to alcohol misuse, childhood stress or violence, serving in the Army, junior ranks and being near to wounding/ death if deployed to Iraq and/or Afghanistan. Violent combat – defined as encountering arms, mortars and/or improvised explosive devices (IEDs) – did not appear to ‘cause’ symptoms, but these exposures appeared to prevent recovery. Perceiving support from both the military and the social group (military and civilian) might be protective against developing symptoms. As evident from other studies too, social support was particularly important.

Aim 2 Lived experiences of how PTSD develops: Key findings

We adopted a different approach to complement these analyses in a second part of the study. This involved interviewing ex-serving personnel who deployed to Iraq/Afghanistan in combat roles to gain first-hand insights of how PTSD develops in people’s experiences. Our sample included 10 participants with PTSD symptoms and seven without symptoms. This allowed us to collect in-depth life histories from childhood to the present day and map participants’ traumatic experiences and when and how symptoms developed.

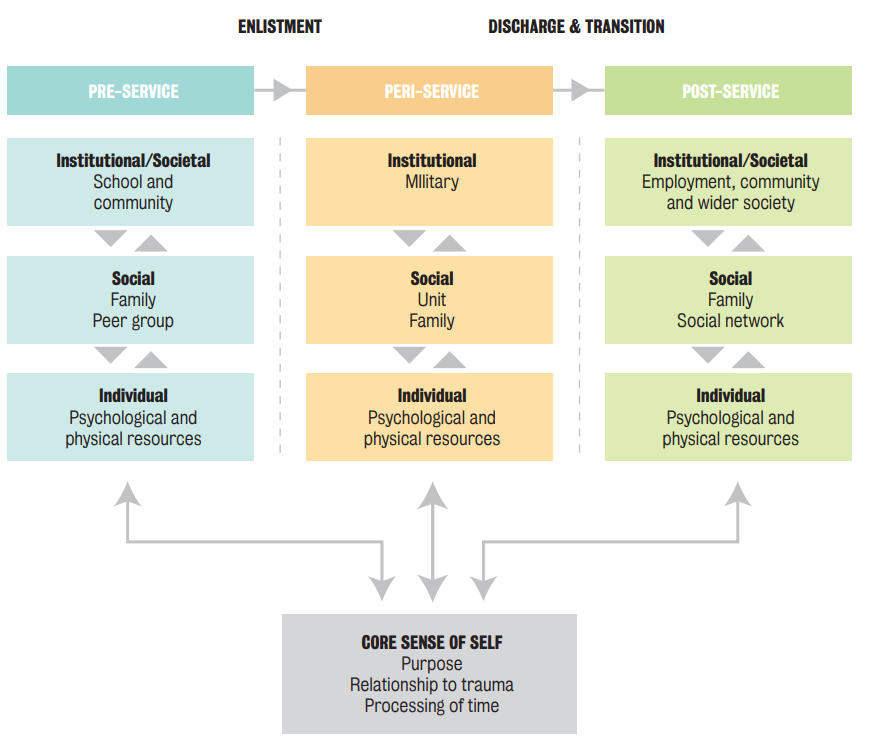

We presented the concept, ‘military holding’ to describe a range of military support structures on institutional (e.g. supportive leadership), social (e.g. kinship of the unit) and individual levels (e.g. compartmentalising and pressing on with the job). Not only were these practical supports, but the military also provided a system of ethics, language and cultural norms that allowed personnel to make sense of very challenging combat experiences.

The wrap-around nature of military life meant that trauma faced during childhood or on deployment was often held, or contained whilst participants were in service. This meant PTSD symptoms often did not develop directly after difficult deployments and, though initial signs of PTSD started in service (e.g. anger, personality changes, emotional numbing/withdrawal), symptoms and the consequences of trauma were largely held at bay.

When participants left the military, and the supports described, symptoms intensified, and traumatic experiences surfaced in flashbacks, nightmares and being triggered by sights and sounds. We propose that these experiences started to arise because of the loss of military holding - not least a culture where deployment trauma was normal, shared and explainable. In post-service life, individuals often found it hard to find their own sources of support and the family became central - a lynchpin - replacing both the social bonds of the unit and sometimes physical and mental health care.

We explained these processes in the ecological model of PTSD symptom development - the ‘ecological’ focus showing how the wider environment and external world might influence whether individuals experience PTSD.

What did we learn ?

We were able to identify the main patterns of PTSD in a large sample of personnel from all branches over a long time-period. Our focused analysis, employing very different methods, meant we were able to explore the actual lived experiences of the most at-risk group of the Armed Forces. We note that this might not reflect all experiences of PTSD, but this was an important first step to understanding why rates might be higher in this group.

We were able to show via our ecological model that PTSD is not confined to the individual, but is a process involving a wide range of social, institutional and ethical factors. Broadening our understanding this way could 1) open up thinking to include other avenues of potential support, and 2) might alleviate some of the stigma individuals might experience surrounding mental health issues, i.e. feeling to blame or flawed. The ‘military holding’ concept – which chimes with others in psychotherapy (see footnote 2) - might also highlight the military’s role in providing something similar to parental attachment, especially for younger recruits.

So, what can be done?

- The Armed Forces, and other occupations like the blue light services, need to consider the long-term effects of having their workers in roles which may require them to compartmentalise traumatic incidents. Our research indicates compartmentalisation may get in the way of processing traumatic experiences in a ‘healthy way’ and it may lead to longer-term suppression;

- That PTSD affects the family so specifically shows how important it is to make sure civilian holding structures are spread across other areas, like employment, community, social groups and, if needed, formal support services.

- Our research points to the importance of easing transition so discharge does not disrupt all holding supports in life. This is not to say that personnel should not aim for a full transition to civilian life, but that personnel should be supported in finding/ building scaffolds in their civilian lives that can help them manage the transition from service and the potential for deployment trauma to arise well into post-service life.

References

- Fear N, Jones M, Murphy D, Hull L, Iversen A, Coker B, et al. What are the consequences of deployment to Iraq and Afghanistan on the mental health of the UK armed forces? A cohort study. Lancet. 2010;375:1783-97.

- Hotopf M, Hull L, Fear N, Browne T, Horn O, Iversen A, et al. The health of UK military personnel who deployed to the 2003 Iraq war: a cohort study. Lancet. 2006;367(1731-1741).

- Latter J, Powell T, Ward N. Public perceptions of veterans and the armed forces. 2018.

- Stevelink S, Jones M, Hull L, Pernet D, MacCrimmon S, Goodwin L, et al. Mental health outcomes at the end of the British involvement in the Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts: a cohort study. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2018;0:1-8.

- Winnicott D. The Theory of the Parent-Infant Relationship1. The International Journal of Psychoanalysis. 1960;41:585-95

[1] The sample comprises Tri-service deployed and non-deployed, regular and reserve personnel. There have been three phases of the cohort study (2004-6; 2007-9 and 2014-16) and all data were collected independent to the Ministry of Defence. The key papers of this study are included in the References.

[2] See Winnicott’s ‘holding’ concept